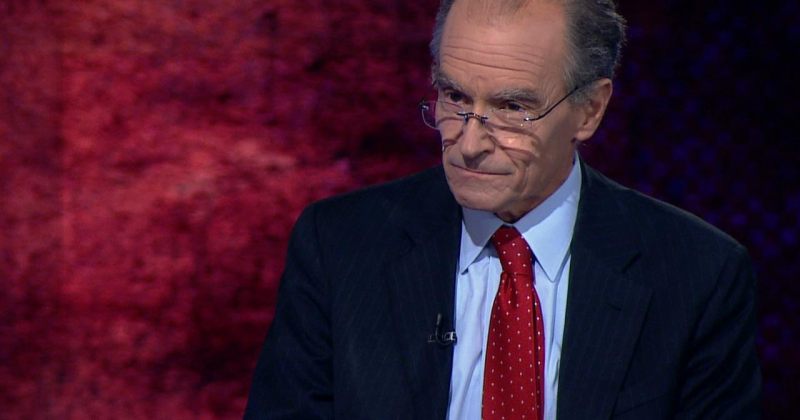

Liam Fox, Conservative Member of the British Parliament and until a few months ago Britain’s Secretary of State for Defense, paid a two-day visit to Georgia in early-January. While here, Dr. Fox met with high-level Georgian officials and representatives of civil society. He also traveled to the administrative border with South Ossetia to observe the situation along the “line of occupation” between “free Georgia” and “occupied Georgia.” In his interview with Tabula, the British MP shared his thoughts about the situation in Georgia as well as important developments in the world.

What is the purpose of your trip to Georgia?

Well, this trip was agreed some time ago. I was very keen to come to Georgia. I had an invitation from the [Georgian] President. Political events have made me postpone more than once though. This was the first opportunity to come, and I have been really wanting to come here since 2008.

Was your desire to come here in 2008 because of the war?

Yes. We had a lot of political friends here [with whom] we were in touch. They were describing events in real time to us, which, of course, ultimately resulted in [British Prime Minister] David Cameron’s visit which I think was both decisive and courageous. We’ve taken a great interest in what has been happening here – not only because of the history of how Georgia emerged from the Soviet Union, but also the way [Georgia has] tried to systematically dupe corruption, the way that [Georgia has] taken a very free-enterprise view of economic structures. By the way, I am, of course, deeply sympathetic to [those reforms].

You just visited the occupation line. Obviously, there is not much Georgia can do to change the situation without the help of the international community. Are you satisfied with those efforts?

The international community can do two things. One is to redouble its effort to make sure that the agreements already reached are applicable. I mean, there are agreements already in place that are being ignored, and we need to be very clear that we expect them to be honored.

Secondly, we have to raise our voices to ensure that liberty and freedom and democracy that are taking root here are properly defended – and that people know that you have international allies who take strong interest in what is happening here.

I said tonight, when speaking at the Europe House, that the international community already has accepted limits for territorial integrity for Georgia. And yet, inside those territorial limits, we stand and watch the foreign flag flying over a checkpoint. If that is not an occupation, what do you call it?

What can you say about the political system in Georgia? Many observers are concerned about the fact that political opposition is pretty weak and they sometimes blame it on the government.

I think a point worth thinking on a regular basis is that democracy just can’t exist in a vacuum. It needs other elements to support it. It needs a rule of law that applies equally to the governing and the governed. And it requires a concept of rights that is genuine and sticks to equality of sex, gender and religion. It needs a proper economic framework in which people can exercise their economic liberty. Beyond that, it also requires the constitutional democracy to have an understanding that opposition and a vibrant, constructive opposition lead to better government; that wider media ownership that allows criticism leads to politicians raising their game. All these things are part of nurturing a vibrant democracy. The measurement of democratic success is not how much politicians enjoy it, it’s how much the electorate is able to change it.

How do you see the European Union both in the short term and in the long term? And where do you see the UK?

I think the European Union needs to understand that it’s no longer the center of global economy. It’s no longer the center of global politics. It’s an important player in both, but too many European politicians have maps on their wall with the Greenwich meridian in the middle whereas American politicians and Asian politicians have the international dateline in the middle, which is much closer to the economic and political center nowadays. So Europe needs to take a more expansive view: It needs to recognize that “European Union” and “Europe” are not synonymous; it needs to look to see how it can make itself competitive in a global context; and so, it needs to be much more expansive and much less self-obsessed.

The UK has upset Germany and France by blocking the new EU Treaty that was supposed to resolve the Euro crisis. What’s your take on that?

We looked for assurances that any changes would not disadvantage the city of London. These were relatively small things to ask for. We didn’t get them. Our European partners already are used to, in [Britain’s] Conservative government, when the leader says something he does it, rather than making empty threats. We made our position clear before the summit [in Brussels]. We didn’t get what we wanted, and we did what we said we would do - veto the treaty.

The single currency – Britain is not a member as we opted out from the start; our view was that the project was ill-founded – the currency had membership which included those countries that had failed to meet the convergence criteria. And then to make matters worse, when those countries were inside the currency, the governments were allowed to follow a fiscal policy that actually led them on a divergent path, rather than a convergent one. So it led to the inevitable, to where we are today.

When you have European countries inconsistently living beyond their means, abandoning the concept of sound money and leaving it to the rest of the world to be concerned about their standard of living, then you inevitably will get to the point where the party is over. And that’s where we are now.

What about the future of the Euro?

Well, it depends. It depends whether our European partners think it’s an economic project or a political project. I think the chance of Greece following an externally imposed austerity program of the scale being described as “normal” is offensive.

About enlargement of the European Union – there is certain fatigue with the enlargement. Do you see it coming in the foreseeable future – within the next ten years, let’s say?

We, the Conservative Party, have been in favor of enlargement. We were very strongly in favor of Turkish membership. Of course, in other European capitals – particularly Berlin, Paris and Vienna – they took a very different view. They were very negative about Turkish membership. I think that the European Union will live to regret blocking the Turkish membership. I think that Turkey is of such strategic importance at a major crossroads between north, south, east and west that we will find ourselves strategically disadvantaged because of xenophobia in certain European countries. As a result, Turkey is going to drift away from its desire to join the European Union, which is a pity. I still think that is an object worth pursuing. I think countries like Georgia, in particular, which clearly have a long-standing feeling for the West, for Europe, should be encouraged in the reform process to believe that it could potentially one day join the European Union.

Interestingly, I was in the theater the other night in Tbilisi and it would be very easy to believe that you were in Budapest or another European capital.

There has always been a special relationship between the United States and the UK. Where do these special relations stand at the moment?

I think there has been a lot of misunderstanding of what this special relationship is. And the first time this expression was used was by Winston Churchill in his speech in Fulton, Missouri, which, of course, is better remembered for the use of the phrase “Iron Curtain.” That’s where he also talked about a special relationship. He talked about this special relationship as a wartime leader who understood the value of sharing intelligence, sharing military practice, even sharing procurement with a commonality.

That has not changed. I think it’s very important to recognize that special relationship is more important than the personal chemistry between any respective leaders or the relationship between whichever party happens to be in power. It supersedes that, is more important than any of those things.

President Obama’s Administration started the reset policy with Russia, hoping to settle relationships. How would you evaluate the results of the reset policy?

It is difficult to measure that in such a short-time span. I think there is value in trying to seek rapprochement in relations. Relations between Britain and Moscow are a bit more frosty. And while we want to work out our relationship, there are issues – such as [exiled Russian dissident Alexander] Litvinenko’s murder [in London] – that we cannot simply draw a line, not on that. The murder of our citizens by a foreign power in our own capital is not something we just overlook.

So I think that what Moscow, what Russian politicians are missing sometime is consistency in the approach and strength in the approach. And I think that inconsistent messages or messages of ill intent are viewed as weakness and are unlikely to produce what we want. So I think, in the long term, we have to decide what we want our relationship with Moscow to be. My view would be to have a business-like relationship until we reach the point (which I think at some time is inevitable) when a new generation of Russians recognize that what they have in common with the West is infinitely greater than any differences that they have. And if you think about it, the longer-term threat to security comes from the South and the East, rather than the West. As long as we still have the current generation who maintain the pretense that NATO is somehow a threat to Russia, it will be very hard to have a genuine “reset” of relations.

You just mentioned the new generation of Russians. What about protests in Moscow, where are they leading?

I see this as being genuinely significant. The events that we now choose to describe as “the Arab Spring” were primarily motivated by big-price hikes in basic commodities and food and fuel. The political unrest added to that, but it was not the prime mover. In Russia, it is political resentment that is a prime mover in this process, which is why I think it is, in many ways, more significant. And I think that the Russian leadership will be worried that there is a generation of young people who, notwithstanding the fact that they may be more affluent, are nonetheless unwilling to put up with the political situation in which they find themselves – not least because they can access the Internet and see what political freedoms are being enjoyed elsewhere. Just as the printing press posed a threat to the medieval church, so the Internet and the freedom of communication we now have and the range of electronic media cause a threat to those who would use the restriction of information as a tool to maintain autocracy. That is the new revolutionary element that we face nowadays.

I think that the ability to control information is just as surely being lost by oligarchs, autocrats today as they were by the medieval church.

Tell me about the Arab Spring. It has been more than a year now since the revolutions have taken place in the East. How can you evaluate the ongoing process from this point?

I think it has provided people who live there with the opportunity to shape their own destiny. But I think it would be very simplistic of us to believe that, overall, it will be shaped in one direction or in any one direction in the short term. I think in the long term they are more likely to be a more pluralistic society based more upon the free-market model. But it took us a long time to develop the political systems and economic systems that we today take for granted. And I think it would be naïve and historically mistaken to believe that these systems will be reproduced in the short term, especially in states which have no history either of meritocracy or free markets or the political institutions which underpin the democracy that we have.

Do you think the fragile peace in the region is safe with the new revolutionary leaders?

I think that this idea – supporting those who are pro-West though nonetheless repressing their people – was a very short-term outlook. There was always going to be change. It is far better that people of those countries understand that the change was supported by the West and international community rather than resisted by us. That is far more likely to produce a relationship where we are able to help shape debate …

Do you think the West is ready to invest in reshaping the leaderships of those countries?

I think so. I think that the easiest test case for that would be Libya. The military campaign in Libya went out of its way to minimize civilian casualties, to not target civilian infrastructure and, therefore, to do two things: one, to show we have higher respect for life and the value of life than the outgoing regime did; secondly, to give them the best chance possible to be able to kick-start their economy with their civil infrastructure intact. And I think that, with our help, Libya is a very good candidate as a country that should be able to economically act quite quickly. If, as I think is likely, [Libya] turns to the United Kingdom, to France, to Italy, to provide economic systems and economic expertise and it is able to develop some of the enormous natural resources, it has not least phenomenal potential for tourism development on the Mediterranean. I think Libya can easily be a major success story.

What is the major threat right now to the West?

I think we face a continued economic threat of instability unless we put our house in order and we have a better balance in the world between the debtors and creditors. That requires a lot of belt-tightening in the West – that is one. I think we face a continued threat of transnational terrorism, and I think we need to understand that not everyone is rational and not everyone can be appeased. Western countries find it difficult to deal with the concept of extremism because they have tried to eradicate it from their own political systems. But it exists and is an ever-present danger. We also, I think, need to be aware of the real threat of nuclear proliferation. We have seen how North Korea has been emboldened by acquisition of nuclear weapons. The last thing we want to do is to see that happen in Iran. I fear that, if Iran becomes a nuclear weapon state, other countries will follow and the chance of nuclear weapons being used in anger in my lifetime will be enormously increased. And I think that would be a failure of the inheritance we provide for the next generation.

Is there anything the West can do apart from UN sanctions?

We need to enforce sanctions. There is no point in having sanctions which are not properly enforced. There has to be a united front – and that has to hurt the regime and hurt those who profit from the regime – to make very clear to all Western countries that they cannot exempt sanctions of their economy because it suits them. Then I think that we have to make it very clear to our allies in the region that we will stand by them, that we will give them security guarantees and we will maintain our robust military presence in the region.

What about Afghanistan? Do you think the Afghanistan government is ready to take over after ISAF leaves their territory?

By the end of 2014-2015 they will be more ready again. I think it’s important that we define what we mean by “success in Afghanistan” – that it is not building a shiny city on the hill enriched by Jeffersonian democracy; it is a stable-enough Afghanistan able to manage its internal and external security without the need of recourse to outside forces. It will take a long time in a place like Afghanistan to develop the sort of institutions we take for granted. We will be required to have a great deal of strategic patience, and we’ll need to be willing to be there to assist the country through a long period of development in its security structures, in its economic and social structures, long after our troops are departed.

Many complain NATO is dying, that it could not resolve its identity issue. What do you think about that?

I think NATO will benefit from robust internal debate. In the wake of the Libya campaign, we saw how NATO was able to set up command-and-control mechanisms quite quickly and to produce a military effect sufficient to carry out the mission it set itself. We also saw, however, some serious problems inside the political structure of NATO. The absence of some of the major players, not just from the military scene but from the diplomatic corps of the United Nations, leads many of us to raise questions about not only the military health of NATO but the political robustness of NATO. And when we get to the NATO summit in Chicago, those questions will need to be asked in a very explicit way and answers forthcoming. So I think that there were big pluses that came out of Libya, but there are minuses that need to be dealt with and which NATO cannot afford to sweep under the carpet.

Do you think there will be some step forward taken in relation to Georgia at the Chicago summit?

Oh, there is some movement. My personal views have always been that to link Ukraine and Georgia was a mistake because they are two very different cases: They are different politically; they are different militarily. Georgia is much more ready to be considered as partway towards NATO, and I hope that at the summit there is a greater clarity given to what NATO wants and expects of Georgia in that process. But exactly what will happen at that summit, what the priorities will be at that point – it occurs at times of enormous uncertainty with the Russian presidential election, the French presidential election and the upcoming American presidential election — who knows whether we will see changes in the leadership in China, who knows what the Iranian situation will be at that time. One cannot predict now what the agenda is going to be at the time we reach Chicago.